JPG Les Tatouages: Redefining Professionalism

written by Ashna Aravinthan

A s a fashion house, Jean-Paul Gaultier should be remembered not for its contributions to the

world of couture, which are, admittedly, beautiful and one-of-a-kind, but rather for the quintessential rebellious nature most evident in

their ready-to-wear shows. The essence of the house lies in its cross-cultural meshing and adamant refusal to conform to societal norms,

both of which are the lifeblood of true street style. There is no show that better encapsulates this understanding of, and respect and

appreciation for, marginal and youth cultures, than his 1994 spring ready-to-wear collection, Les Tatouages.

With the 1990s came the first fully formed

sociological conception of fashion: the “trickle-down theory”, positioning lower classes as constantly in awe of upper classes and always seeking

to emulate their luxury and prosperity through imitating what they wore.1

This theory relied on the upper classes as avant-garde revolutionaries able to put together new and innovative looks, when in reality,

their ‘fashion sense’ more often than not was a result of having the money to buy styles fresh off the runway. Les Tatouages is a

direct rejection of that popularised ideal, instead recognising the value of street styles prominent in ‘inferior’ classes – making

a point that fashion standards were generally percolated up and appropriated by the rich, rather than being tastelessly duplicated by the

poor.2

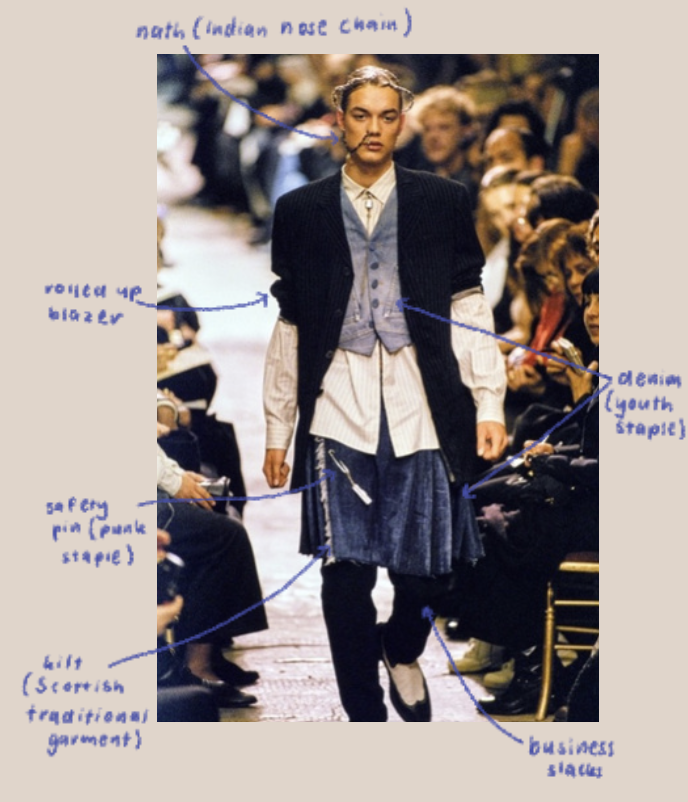

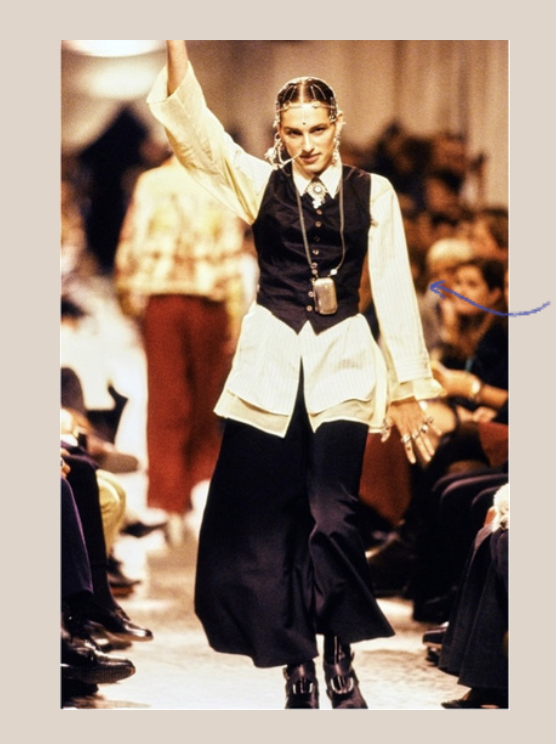

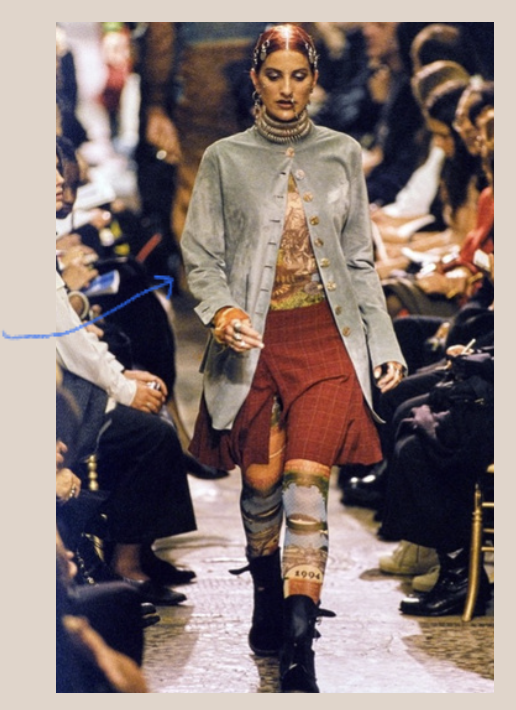

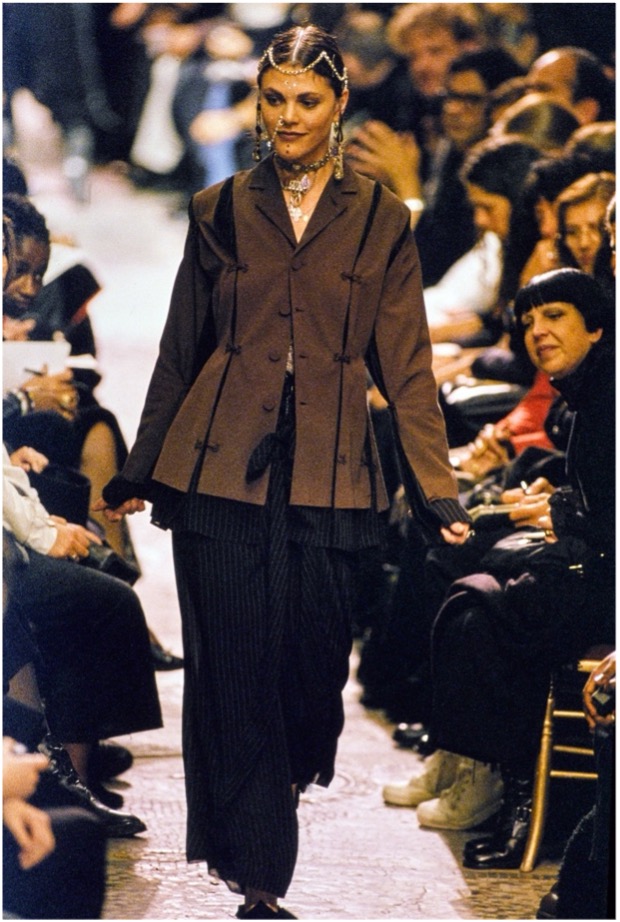

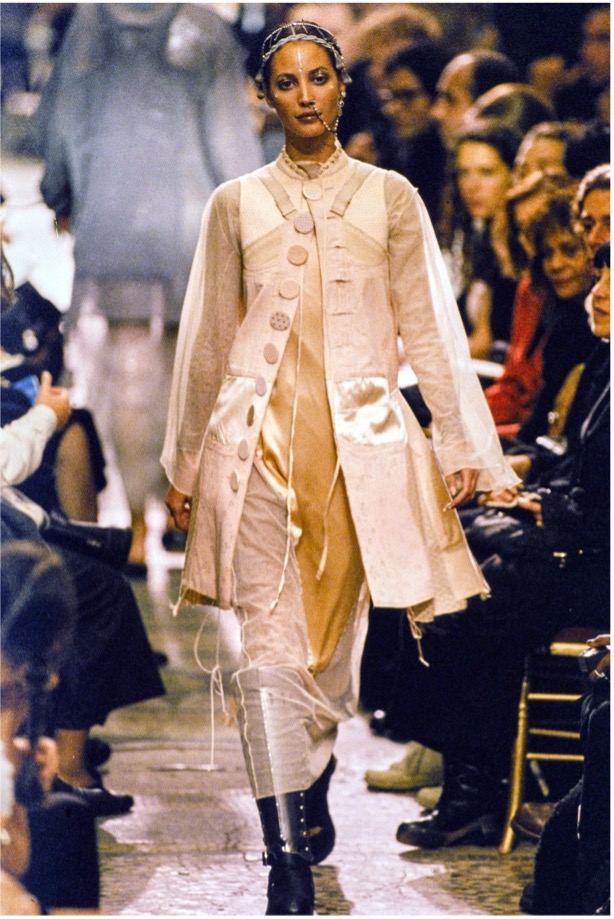

D isparate elements of marginal and youth cultures are pulled together to create shocking and unconventional looks that cheekily reference and defy the boundaries of professionalism as defined by the upper class. Even the models themselves are emblematic of this desire for upheaval in our social structure – it is clear they come from a range of cultural backgrounds, which is quite striking considering this was an era were models were mostly white. Many of them sport evident tattoos or piercings, something which even today is warned against if people are seeking to break into the modelling industry. Short skirts, exposed midriffs, low waistlines, bare shoulders, high heels, lurid and artificial colours synonymous with youth culture are presented alongside the classic white business shirts, suspenders, and grey suit pants customary to the modern-day workforce.

But of course, the Western office ideal is hopelessly outshine by the delicate intricacy of their maximalist pairings which draw from marginal cultures: a waistcoat worn with heavy facial jewellery rather than a pocket chain, body hugging trompe l’oeil shirts emulating tribal body tattoos worn under the oversized cardigans one might bring to protect against ever-chilly office air-conditioning. The officewear never seems out of place but is always complemented by pieces that you may never have imagined together, and suddenly it feels like these combinations were meant to be.

the 9 - 5

followed by

the 5 - 9

Historically, we’ve seen evidence for the trickle-up effect, which, as the name suggests, is the antithesis of the trickle-down effect. The British made fortunes off of ripping off Indian textile-makers and reappropriating their muslin, a fabric which quickly became a symbol of status in the Western world. Body art tattoos have a rich tribal history across multiple cultures, but are today mainly seen as an aesthetic, and often selected against by hiring managers, who believe tattoos are an indicator of unprofessionalism. Fashion is even today being influenced by marginal cultures with little recognition. Last year’s Scandinavian shawl trend was simply re-naming South Asian dupattas, and the mesh shoes worn by it-girls have also been worn by East Asian grandmas for years. Our fashion always has been, and will always continue to be, inspired by marginal cultures, but it’s rare for these marginal cultures to be acknowledged or fully accepted into the spotlight. This is a large reason why aspects of marginal cultures are viewed as unprofessional or undesirable today, despite being the basis for many of our current norms. Les Tatouages not only pulled from marginal cultures, but actively recognised them and embraced them within its Western perspective – the show symbolises harmony unparalleled in our current social climate.

References

1 Fred Davis, “Herbert Blumer and the Study of Fashion. A Reminiscence and Critique”, Symb. Interact, 14 (1991), cited in Patrick Aspers and Frèdèric Godart, “Sociology of Fashion: Order and Change”, Annual Review of Sociology 39 (2013): 179.

2 Paul Blumberg, “The Decline and Fall of the Status Symbol: Some Thoughts on Status in a Post-Industrial Society”, Social Problems, 21, no. 4 (April 1974): 493.